A brief history of woodturning

Introduction

Information about woodturning before the 13th century AD is

sparse. What information we have is derived from:

1) a single pictorial representation of a lathe from the 3rd

century BC;

2) a few references to lathes and turning in Greek and Roman

literature; and

3) a limited quantity of the physical remains of turned

products and turned waste.

Because of the last of these we know that woodturning has been

practised from at least the 6th century BC and possibly for

several hundred years prior to that. Although the information

on the early development of woodturning is sparse it is

surprising how much it tells us when it is interpreted in the

light of information from later periods. Our story will begin

with the lathe.

|

Products of the lathe

Fig 1: The Mycenean Wooden Bowl

Fig 1: The Mycenean Wooden Bowl

Circa 1200 BC

|

|

It has been seen that the first evidence of the lathe itself

comes from the 3rd century BC but it is known that it was in

use long before that. A flat wooden dish which stood on wooden

legs was found in a pit grave at Mycenae dated at 1100 to 1400

BC. This dish has low side walks with a bead running around the

top, which is typical of turned work. There is also a hole in

the centre, which has been plugged. This suggests that it could

have been turned on a mandrel held between centres in a lathe.

Against this view must be set the fact that there is no sign of

turned grooves on the piece.

|

Fig 2: Part of a bowl found at Corneto

Fig 2: Part of a bowl found at Corneto

Dated as from 700 BC

|

|

When we move forward in time a few hundred years we find

clear evidence that the Etruscans (who lived in the region

which is now northern Italy) possessed well developed

techniques of turning. The earliest piece from that area was

found at a site known as the "Tomb of the Warrior" at Corneto.

This is a fragment of a wooden bowl, dated at around 700 BC,

which shows "clear evidence of rounding and polishing on its

outer surface and of hollow turning..." (Woodbury) Other

Etruscan turned vessels were found on this site. |

|

|

The next few generations of Etruscans must have continued to

develop the skills of their forefathers. Examples of their work

from the 6th century BC have been found in substantial

quantities. These include turned ornaments for hairpins, amber

beads and some turned wooden platters.

The Etruscans were not the only people to use the lathe in that

period. Excavations of a mound grave in Asia Minor (now Turkey)

revealed two flat wooden dishes with decorative turned rims.

These have been dated as from the 7th century BC. A number of

turned wooden boxes and bowls from the 5th century BC have been

found in the Crimea. One of these is described by Woodbury as a

"double box" made in one piece with a separate cover which

"shows highly sophisticated skills in turning". |

Fig 3: Bowl found at Uffing in Upper Bavaria

Fig 3: Bowl found at Uffing in Upper Bavaria

Dated as from 6th C. BC

|

|

The oldest complete turned artefact discovered was a bowl

from about the 6th century BC that was found in the late 19th

century by Julius Naue in a burial ground at Uffing in Upper

Bavaria. Although the early turner's equipment was, of

necessity, very primitive this does not mean that the turner

was lacking in ability; this bowl provides strong evidence of

very considerable skill. It is not simply a utilitarian piece,

such as those, which were produced, in great quantity in

England in Medieval times, but takes the form of a goblet with

a stem and base. Not only was it decorated with beads but it

also had a large captive ring around the stem. It was a very

sophisticated article to have been produced by such primitive

means.

How much more difficult was turning for him than it is for us;

what kind of lathe did he use? This question provides a

convenient link to the consideration of the history of the

lathe itself, rather than at the objects that were made on it.

|

The history of the lathe

Types of lathe

(1) The strap lathe

(2) The bow lathe

(3) The pole lathe

(4) The great Wheel

(5) The treadle lathe

|

|

|

The list in the box on the left represents a very

rough attempt to set out the chronological development of the

lathe. It is imprecise because no-one knows exactly at what

date any of them first came into existence. It should also be

noted that the earlier lathes were not made obsolete as soon as

a new type came into existence. Indeed, examples of all of them

can be found in very modern times.

One aspect of the problem of dating is that no physical remains

of the lathe itself have been found from before the 10th

century AD, at the very earliest. The only evidence we have of

the nature of early lathes is that of a documentary nature.

|

The strap lathe

Fig 4: Schematic diagram of a strap

lathe

(tool rest not shown)

Fig 4: Schematic diagram of a strap

lathe

(tool rest not shown)

|

|

On these lathes the work-piece is held between two iron spikes

supported by a crude wooden framework. The tool rest is formed

by a long rod, which runs parallel to the axis. The motive

power is transmitted by a strap which takes a couple of turns

around the end of the work-piece; the strap is pulled backwards

and forwards by the turner's assistant to provide a

reciprocating motion. Usually, both the turner and his

assistant had to sit on the ground to operate this device. |

Fig 5: Depiction of turmer at work - 3rd C.

BC

|

|

A turner from ancient Egypt

The earliest information on the lathe dates from the 3rd

century BC. This is a bas-relief carving on the wall of the

grave of an Egyptian called Petrosiris. This carving shows a

craftsman and his assistant busy on a bow lathe very similar to

those, which have been found in use in Egypt in modern times.

|

|

|

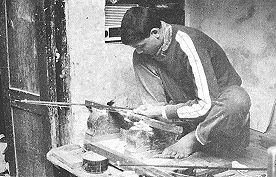

The image on the left which is taken from a book published in

1881 (Hand or Simple Turning - Principles and Practice by John

Holtzapffel) portrays an Indian turner. The author states that

"He commences by digging two holes in the ground at a distance

suitable for the length of the work, and in these fixes two

short wooden posts, securing them as firmly as he can by

ramming earth and driving in wedges and stones around them. The

centres, scarcely more then round nails or spikes, are driven

through the posts at about eight inches from the ground, and a

wooden rod for the support of the tools, is either nailed to

the posts or tied to them by a piece of coir or coconut rope.

The bar if long is additionally supported ... by one or two

vertical sticks driven into the ground. During most of his

mechanical operations the Indian workman is seated on the

ground ... The boy, who gives motion to the work, sits or

kneels on the other side of it holding the ends of cord wrapped

around it in his hands, pulling them alternately ...". Notice

that in this instance the turner is using his toes to steady

the tool on the rest. |

|

|

A lathe of a very similar type was still in use

in Ethiopia in the late 1960's when Nancy Boothby (an American

teacher) took the photographs on the left showing the bowl

turner at work. (Please note that the copyright to the images

shown in Fig.s 7a to 7g is owned by Taunton Press. These images

are reproduced here with its permission.) Fig 7a shows the work

piece held between centres made by driving two 6 inch metal

spikes into logs embedded in the ground. The end the tool rest

support was placed on one of the metal centres and the tool

rest itself was laid across that. the turner held the rest in

place with his feet. The assistant pulled forward and back on a

leather strap wrapped around the mandrel. |

|

|

|

The Ethiopian bowl maker did the shaping with a

primitive axe/adze. This had three interchangeable socketed

heads which fitted on a single crooked handle. the handle was

made utilising the natural shape of a branch. This device was

similar to those used by the ancient Egyptians. But the latter

did not have a socketed head, instead the flat blade was lashed

onto the handle with leather or sinew. However, it is thought

that a socketed head was used in parts of Asia in the ancient

world. |

|

|

|

Turning by these methods is very heavy work so

to reduce the effort the blank is shaped as much as possible,

inside as well as out, before it is turned. However, because

the bowl is held between centres a spigot is left in the middle

of the inside until the turning is completed. Similar

roughouts, from the late Iron Age, have been found in Britain.

|

|

|

|

With the roughout held between his feet the bowl

turner drilled a hole in the centre of the bottom. The drill,

which could hardly have been more primitive, was simply rolled

between his hands. |

|

|

|

The mandrel was then driven securely into the

bottom of the roughout. The mandrel was a piece of branch wood

with a tapered end sheathed in metal. The metal sheath is not

essential but it speeds up the process - without it time would

have to be spent making a mortise and tenon joint. |

|

|

The bowl was then turned. Local abrasive leaves, probably

from the fig tree, were used for sanding. But little sanding

was required because of the smoothness of the cuts. The knobs

on the top and the bottom were finally removed with the adze

and the rough areas smoothed over with the turning tool.

|

The Bow Lathe

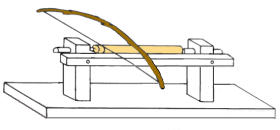

Fig 8: Schematic diagram of bow

lathe

Fig 8: Schematic diagram of bow

lathe

|

|

The bow lathe is very similar to the strap lathe

but the motive power is supplied by a bow. The string of the

bow is wrapped around the work piece and a reciprocating motion

is created by moving the bow backwards and forwards. Whereas

the strap lathe requires two people to work it the bow lathe

requires only one. The drawback is that less power is available

and the turner has only one hand with which to control the

tool. In some cases the turner used his foot to help to steady

the the tool. Because of these deficiencies only small work is

done on the bow lathe. |

|

|

|

Turning backgammon and chess pieces

with a bow lathe.

From King Alonso X's Book of games of 1283 |

|

|

|

Fig 10 on the left shows a Persian turner at

work on a bow lathe as described by Holtzapffel: "In his lathe

the centres are made to pass through the the ends of an open

box the edge of which serves as the support for the tool; they

are raised or lowered to suit work of different diameters in a

series of holes pieced in a vertical line. Small works are set

in motion by the bow, both by the Persian and the Indian, for

those of larger diameter, both use a cord pulled by an

assistant |

Fig 11: An Egyptian lathe - 1873

Fig 11: An Egyptian lathe - 1873

|

|

Fig 11 is based on a sketch made by Holtzapffel in a turner's

shop in Cairo in 1873. Although this was crudely constructed it

presented several improvements on the lathes of the Indian and

the Persian turners shown above. It was more robust,

self-contained, adjustable, and portable. Holtzapffel described

the way it was used as follows: "The operator sits upon one

heel, the toes of the foot going just under or upon the

stretcher and he directs the tool, which he holds by a long

handle, with the toes of the other foot .... Occasionally and

for heavy work, both feet are advanced, placed close together,

and press on the tool on the bar by the big toes, the other

toes closely pressed around the tool and on the bar; while the

latter is always pushed forward by the feet ..... . The bow

presented a peculiarity in the hinged piece near the handle,

employed to regulate the tension in the string; the string is

wrapped once or twice around the work, after which it is

twisted around the jointed piece, which is then folded back and

held in the hand with the handle." |

Fig 12: An Egyptian boy at work -

1960's

Larger image

|

|

There is evidence that a bow lathe very similar

to that used by the ancient Egyptians was in use in the same

area in the early 1960's. I have a book, which contains a

photograph of an Egyptian boy working a bow lathe by himself:

his right hand is working the bow, his left hand is

manipulating the tool. It is not clear what he is making but

whatever it is it is very small. |

The pole lathe

Fig 13: Schematic diagram of a pole lathe

Fig 13: Schematic diagram of a pole lathe

(The tool rest and other features are omitted)

|

|

The pole lathe was invented sometime before the 13th century

AD. Although it represented a great advance the pole lathe was

not that much more complicated than its predecessors. The

differences consisted of a framework to raise the bed of the

lathe clear of the ground, the addition of a pole and a

treadle. The basic construction is shown in the diagram. It can

be seen that the upper end of the driving cord is attached to

the tip of a flexible pole and the other end is fastened to a

simple treadle arrangement below the bed of the lathe. It

should be noted that function of the pole is to act as a return

spring and to keep the string taught - nothing more.

For its time this was a major technological breakthrough; it

not only freed the turner from the need for an assistant but

also enabled him to stand instead of having to sit on the

ground. Together these factors gave him more control over the

process; they made it possible for him to control the rhythm of

work, to apply more power and to exercise greater freedom of

movement. Many of these early lathes would have been portable

enabling them to be set up near the raw material, or near the

customer, whichever was the more convenient. Others, however,

particularly those for turning bowls may have been fairly

substantial constructions being heavy and rigid.

|

Fig 12: Stained glass window - 13th C

Fig 12: Stained glass window - 13th C

|

|

It is not known when or where the pole lathe first came into

use. It has been suggested that its origins date back to at

least to the Saxon period in Europe but this is speculation.

The first clear evidence of its use comes from two sources in

the 13th Century. One of these is a manuscript illumination of

a nun turning a bowl and the other is a stained glass window in

Chartres Cathedral. As is to be expected the window does not

provide a very clear picture but we know it shows a turner at

work because it was donated to the Cathedral by the local

Turner's Guild. It must depict a pole lathe because the cord

can be seen running down the centre of the window. |

Fig 15: Manuscript illumination - 13th C.

Fig 15: Manuscript illumination - 13th C.

|

|

Fig. 15 shows a nun at work on what is clearly a

pole lathe. The lathe appears to be of relatively light

construction but this may be due to artistic licence. In common

with many early illustrations of the lathe the tool rest is not

shown.

Source: La Bible Moralisee |

|

|

|

Fig. 16 shows a turner working on a

pole lathe which is much more robust than that shown in Fig.

13. Here, again, the toolrest is not shown. It is not clear

what the tuner is making but it could be the hub of a wheel.

Source: Mendelsches Bruderbuch 1395

|

|

|

|

Fig. 17 is interesting because it depicts some

of the items that the turner had made. These include dishes,

bowls, large spindle turnings, and what appear to be musical

instruments (the latter are on the bench in the foreground on

the left). The large sphere on which the turner is working is a

puzzle: what is it and what would it have been used for? It

does show that large, weighty, objects could be turned on the

pole lathe.

Source: woodcut in the "Panoplia Omnium" by Hartman Schopper,

published at Frankfort-on-the-main in 1568 |

|

|

|

Fig. 18 also shows some of the turner's

products, namely a chair and a spinning wheel. The bowl perched

on top of the headstock would have contained oil that the

turner used to lubricate the metal points holding the

work-piece. This lathe can be compared with the one shown in

Fig.16 above. In the latter the the bed of the lathe is made by

cutting a slot in a heavy board. In this lathe it is made from

separate pieces of timber bolted onto posts - together these

form the frame of the lathe.

On the shelf on the back wall are a number of objects which

have been identified by Pinto as "three footwormers, a spice(?)

box, a yoke, flour barrels, etc." Did the turner make these or

was it just a convenient place to store them?

Source: copper engraving by the Dutch artist Jan Joris Van

Vliet (born at Delft in 1610) |

|

|

|

The illustration of a pole lather on the left is taken from

Joseph Moxon's book "Mechanic Exercises or the Doctrine of

Handy-Works". This was published in 1678 and was the first

English book to describe and illustrate the tools of various

trades and the way they are used; in effect it was the first of

a long line DIY manuals. Moxon's illustration are a little

crude by today's standards because he not only had to prepare

the drawings but engrave the plates himself.

Note the bar in the foreground which rests on two supports.

Moxon tells us that it was called the Seat "not because it was

so but because the Workman places the upper part of his

Buttocks against it, that he may stand the steddier to his

Work, and consequently guide his foot the firmer and exacter".

The use of the seat by pole lathe tuners seems to have been a

matter of personal preference. Some used it, others did not.

|

|

|

|

Fig. 20 shows a turner making a

large baluster. This illustration is from a book published

nearly 90 years after Moxon's. The lathe is essentially the

same as that used by the pole lathe turner in the 1395. (see

Fig. 16)

Source: T. H. Coker and others, The Complete dictionary of

Arts and Sciences (1764-6), Vol. III. |

Fig 21: Schematic diagram of possible Roman lathe

Fig 21: Schematic diagram of possible Roman lathe

|

|

The great

wheel

There is some evidence from a detailed examination of bronze

vessels that the Romans employed lathes using continuous

motion. It has been suggested that the drive could have been

provided by means of a pulley system utilising an independent

"great wheel" as illustrated in Figure 21. (See Caroline

Earwood - Domestic Wooden Artefacts in Britain and Ireland From

Neolithic to Viking Times) |

|

|

|

Fig. 22 shows a great wheel in use

in a pewter turner's work-shop in the middle of the 16th

century. The figure in the background appears to be sitting in

front of a fire wielding a soldering iron. The similarities

between this image and that in Fig 17 showing a pole lathe

turner are striking.

Source: Book of Trades - Jost Amman - 1568 |

|

|

|

A great wheel in a wheelwright's

shop in modern times. Probably used for turning wheel hubs.

Writing in 1881 Holtzapffel says that the great wheel (or as he

calls it the hand fly wheel) "has been very generally

supplanted by power, nevertheless is still remains in use for

many industries, it is convenient for occasional purposes in

all workshops, while it has the recommendation over most

motors, of simplicity and almost impossibility of derangement.

The largest and lightest handwheels are those used by the soft

wood turners; these are made of wood with spokes very like the

wheel of a carriage, and measure from six to eight feet in

diameter." |

Fig 24: Leonardo's lathe c1500.

Fig 24: Leonardo's lathe c1500.

|

|

The treadle, or foot wheel,

lathe

This sketch (Fig. 24) by Leonardo de Vinci is the first known

illustration of a treadle lathe.It is not known whether it is a

drawing of a lathe he had seen or if it is another of his

original concepts. Whichever it is it is not a practical

machine because it would turn too slowly. |

|

|

|

Fig. 25 (Coker ibid) shows how the turning speed

for a treadle lathe was increased by using a flywheel and belt

to drive a small pully on the headstock. Note that the flywheel

and the pulley are provided with a number of stepped grooves so

that a variety of speed ranges could be obtained by moving the

belt.

|

Fig 26: Treadle lathe - late17th C or early 18th

C.

Fig 26: Treadle lathe - late17th C or early 18th

C.

Larger

image

|

|

The lathe shown in Fig. 26 is set up for ornamental turning.

Ornamental turners are able to create patterns on the work and

obtain forms which are not possible with hand turning.

Ornamental turning has always been very much a minority hobby -

in its early days it was practised by by members of the upper

echelons of society, including royalty. It is still done today

by enthusiasts, some of whom use antique machines similar to

the one illustrated here. Good antique machines command very

high prices. Examples of ornamental turnings can be seen on the

website of The society of

Ornamental Turners |

|

|

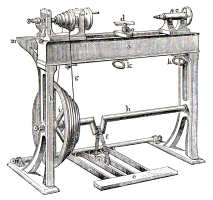

The lathe shown if Fig. 27 is made entirely of

metal and is a robust machine. Despite the existence of such

machines the pole lathe was preferred by many hand turners and

it lingered on well into the 20th century. To quote Holtzapffel

again: "The exclusive or even general use of the footwheel for

the lathe, was probably considerably retarded, first, by the

very simple and economical nature of the pole lathe, and then,

by imperfections in the construction and in the manner in which

the employment of the wheel was first attempted.". After small

electric motors became available treadle lathes became museum

pieces |

Tailpiece

Fig 28 Lathe for turning locomotive wheels in

mid-19th C.

Fig 28 Lathe for turning locomotive wheels in

mid-19th C.

Larger image

This image has been added to provide some perspective. Until

the beginning of the 19th century the tools for turning both

wood and metal were handheld. In the early years of the century

Henry Maudsley developed the slide-rest lathe for turning

metal. The tool was clamped in the rest which slid along an

accurately machined bed and was moved by a leadscrew. With the

implementation of steam power the metal cutting lathe developed

rapidly. The lathe shown above was able to turn two steam

locomotive wheels on their axle.

Source of image: A treatise on Lathes and Turning, W

Henry Northcott, 1868 |

|